The COVID-19 pandemic has created a double challenge: First, an increased sense of urgency to deal with the ravages of the novel coronavirus and the systemic risks that left the world vulnerable to the disease. Second, as economies have faltered and jobs disappeared, and as debt crisis looms, there are fewer resources to meet those challenges.

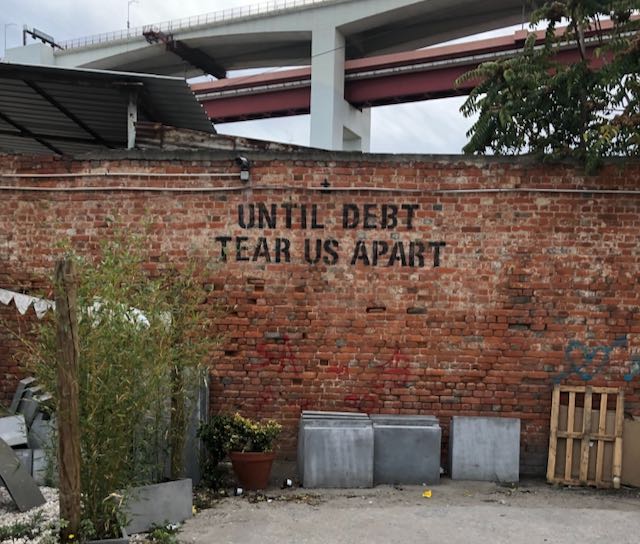

The pandemic-induced global recession will only hurt the ability of households, companies, and countries to service their debt, especially if a new wave of the pandemic lies ahead this fall. In turn, that debt hangover will reduce the ability of the economy to heal, much less to invest in a future that makes crises like the current one less likely.

Bad as it is, the economic impact so far is only the tip of the horn of a gray rhino charging at us: think of the dangerous debt overhang as the bulk of the beast’s weight.

The International Monetary Fund has been warning for quite some time of the dangers of high sovereign and corporate debt, which have been fueled by low interest rates since the Great Financial Crisis. By the end of this year, global gross government debt is expected to be $66 trillion, or 122 percent of GDP. Some countries can more easily bear that than others.

Fitch Ratings Agency notes in a recent report that combined, rating agencies have downgraded 25 countries so far this year, many by more than one notch. In turn, that has lowered the ratings of companies in those countries since companies cannot be rated higher than their home country. It predicts a record number of sovereign defaults this year following in the wake of Argentina, Ecuador and Lebanon.

In May, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs warned that emerging market countries had suffered close to $100 billion in non-resident portfolio outflows this year, and more than 100 countries had asked the IMF for emergency financing. Borrowing costs have gone up even as global interest rates hover near zero, it noted.

In April, a report from United Nations Secretary General warned that low-and middle-income countries are highly vulnerable to debt crisis and along with it the domino effect of capital outflows while losing access to market financing. The report urged a standstill in debt payments for countries that can no longer access capital markets, followed by targeted debt relief, and finally changes in the global sovereign debt architecture.

This month, I joined with others addressing the Global Investors for Sustainable Development Alliance and then the United Nations Global Compact Leaders Summit to talk about the looming global debt crisis and what we can do about it.

COVID-19 has left the world with far fewer financial means to invest in the change we need. But it also may leave us with something even more important, which in turn can open new paths to solutions : a clear vision of the future if we fail to do so and a renewed sense of purpose and urgency in addressing the systemic risks that stand in the way of creating the world as it could be.

I have written extensively, both in THE GRAY RHINO and early on in my career when I covered emerging markets debt restructuring, about how the longer creditors and sovereign borrowers take to resolve debt crises the bigger the damage is. Since Argentina’s 2001 default debacle, many nations and creditors have taken to heart the lessons of the failure to address the crisis before it became a catastrophe.

Economic policy makers and private creditors need to keep that top of mind in swiftly seeking ways to avert the looming debt crisis. As we saw in the 1980s, sovereign debt crises can spread around the world, not so unlike a virus, damaging the portfolios of lenders as well as markets for companies selling in struggling countries. The problem doesn’t stay within the borders of the countries that cannot pay their debts.

The world’s most vulnerable countries need nothing less than debt restructuring on a large scale, with the public and private sector working together closely to swap out unsustainable debt and to replace it with creative financing that supports quality economic growth and the sustainable development goals.

Historically low interest rates and crisis recognition have created an opportunity to buy back existing debt from the most vulnerable countries and re-issue it at lower interest rates under creative new financing structures and triple-bottom-line accounting.

“Social bonds” including “green bonds” can provide funds for needed health, climate change, and other investments supporting the sustainable development goals at a below-market cost, in exchange for commitments that would reduce the likelihood and impact of future crises.

Creditors –including governments, multilateral financial institutions, and the private sector—must switch to a shareholder mindset in which they provide support to get through the crisis and, in return, share in the benefits when growth resumes. After Argentina’s 2001 crisis, there was a lot of talk about GDP linked bonds that would pay higher interest rates during boom times and lower rates during recessions. It’s time to revisit that idea, which can help to prevent defaults during crisis as well as keep economies from overheating and extending a dangerous boom-bust cycle.

We need a long-term fund of patient capital to help countries to grow –which in turn will benefit not just creditors’ lending portfolios but also their other investments that depend on strong, healthy economic growth. This is not charity, as some might say, but rather an investment in the global economy that will create jobs and support markets for goods and services.

This article is part of my LinkedIn newsletter series, “Around My Mind” – a regular walk through the ideas, events, people, and places that kick my synapses into action, sparking sometimes surprising or counter-intuitive connections.

To subscribe to “Around My Mind” and get notifications of new posts, click the blue button on the top right hand on this page. Please don’t be shy about sharing, leaving comments or dropping me a private note with your own reactions.

For more content, including guest posts, please visit www.thegrayrhino.com.

- The Gray Rhino Wrangler on Substack - January 1, 2025

- Gray Rhino Risks and Responses to Watch in 2024 - January 10, 2024

- In the Media 2023 - December 31, 2023