Coverage of the coronavirus outbreak in China includes maddening references to the outbreak as a “black swan” –that is, a high-impact event that is utterly unforeseeable and unmanageable.

Pishposh. Once you can imagine something, by definition it is no longer a black swan. If you can’t imagine that something has happened before cannot happen again, you are the proverbial ostrich with your head stuck deep in the sand.

Coronavirus demonstrates how dangerous it is to rely on the myth of the black swan metaphor, which unfortunately more often gets used as a cop-out than for its intended use: as a call to build more resilient systems.

Given what we know about pandemics and their increasing likelihood, outbreaks are highly probable and high impact. I coined the term “gray rhino” for exactly such events: obvious, visible, coming right at you, with large potential impact and highly probable consequences.

No, we don’t know exactly when or where pandemics will erupt. Nor do we know exactly how they will turn out. That does not mean they are unforeseeable. Very few predictions include that kind of detail –partly because the outcomes depend on how proactive we are in preparing to respond, and whether or not we act quickly.

What we do know is that they will happen. We also know that global air travel –by increasing the likelihood of contact— and climate change –by expanding the habitat of the kinds of mosquitos that carry Dengue, Zika, and other deadly viruses— have increased their potential strength and likelihood of spreading. We also know that overuse of drugs -particularly antibiotics- has led to more drug-resistant strains of infection.

It should not be a surprise that infectious diseases made the top ten risks in terms of impact on this year’s World Economic Forum Global Risks Report.

By some estimates an influenza pandemic like the one that killed my great-grandfather in 1918, today could kill 80 million people and knock 5 percent off of the global economy. And that’s just a strong flu, not a more deadly corona or Ebola type virus.

We also happen to know more than a little about the kinds of things we can do to reduce their danger –but unfortunately have invested too little in best practices.

Pandemics –epidemics that have crossed national borders—have been a constant throughout history, recorded as far back as 430 BC in Athens to the Black Death of the fourteenth century, the European diseases brought by Columbus to the New World and which devastated indigenous populations, and extending through the 1918 Spanish Flu, which killed my great-grandfather. And of course more recently SARS, H1N1, Ebola, and MERS.

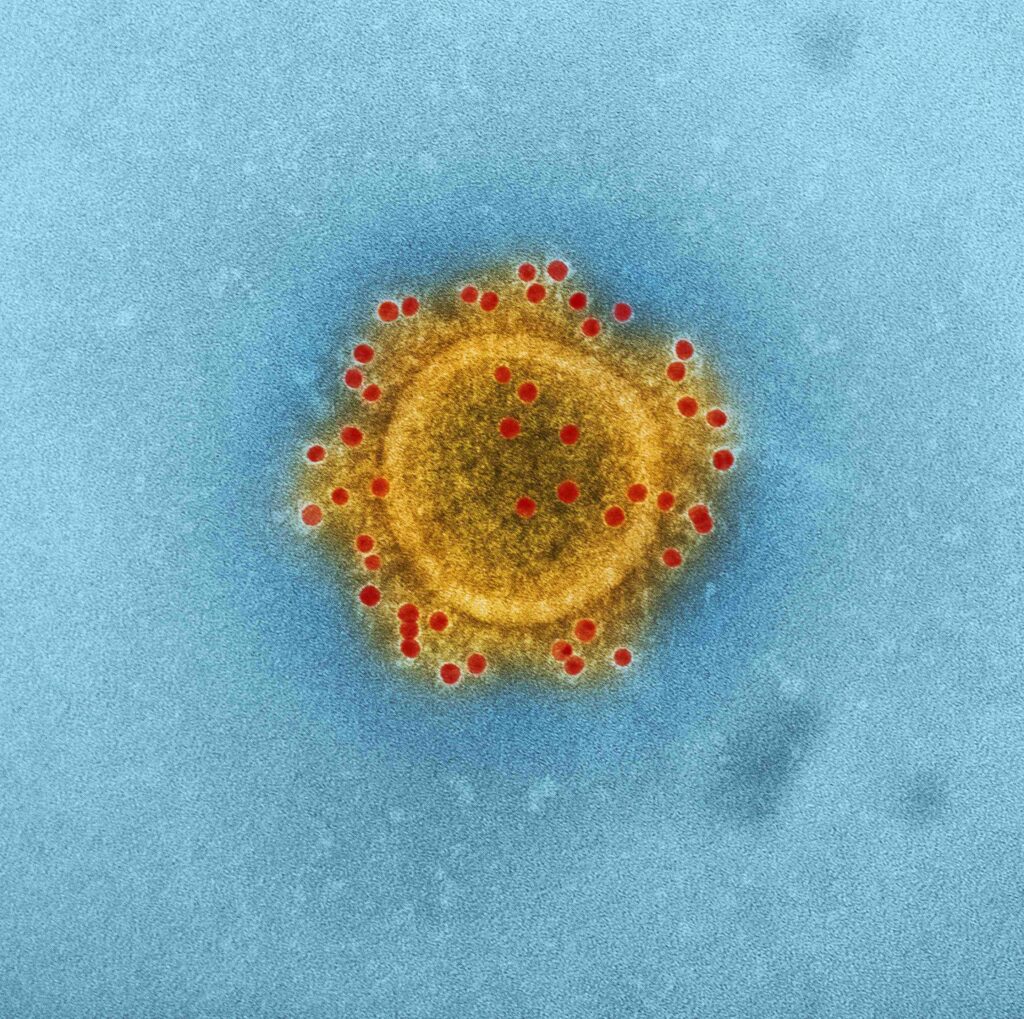

The image above is of MERS to drive home that we have seen outbreaks of deadly viruses before; not only can we imagine them but we have very clear images of what they look like.

The World Health Organization tracked 1483 epidemic events in 172 countries between 2011 and 2018. It has raised the alarm that the world is not prepared for the next pandemic, despite viral outbreaks being such a clear and present danger. In a September 2019 report, WHO called for concrete actions to lessen the risk, including stronger commitments by heads of state, countries, and regional bodies to invest in preparing for pandemics; regularly tracking preparedness; increasing funding, particularly for developing countries with weak health systems; improving international coordination.

The best way to catch outbreaks early and contain them is to have a robust healthcare system. While this is most crucial in developing countries with severe healthcare deficits that mean they have trouble handling the most common issues, don’t think that the United States is immune (so to speak). Far too many people don’t get the health care they need because of the cost. There were about 28 million uninsured non-elderly Americans in 2018. Many people with insurance put off trips to the doctor because of the cost and/or time. Fewer than half of Americans, for example, get the flu vaccine.

As of this writing, more than 80 people have died and more than 3000 coronavirus cases have been confirmed, mostly in Greater China. Along with China, cases have emerged in Singapore, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea, Thailand, Australia, Vietnam, Canada, France, and across the United States, including (yikes) here in Chicago and elsewhere in the United States. By the time you read this, the data will be out of date.

I woke up this morning to read the harrowing account of a friend who had been in Wuhan and developed a cough and slight fever when she returned to Malaysia, and was quarantined in a hospital while waiting what seemed like an interminable amount of time to get her test results –thankfully, negative for coronavirus. “Just” the regular flu.

The World Health organization said on Friday that it’s too early to call the coronavirus a global outbreak. Despite its stated emphasis on preparedness, WHO as of this morning had still not yet called the new coronavirus a global health emergency, citing in part China’s aggressive efforts to contain the virus.

China detected the virus December 29th because it had put in place an early-alert system, and within two weeks had analyzed, identified, and released its genetic code globally. As of January 24, it had quarantined 12 cities with a combined population of 35 million.

The Oslo-based Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations is working on a vaccine which it expects to be able to test on human subjects within 16 weeks.

Some self-styled Western health “experts” on Twitter called China’s quarantine and the rising global concern over the coronavirus an over-reaction, noting that the flu kills many more people each year than those identified to date. After all, the CDC’s annual flu burden report for the current season reports that as of January 18 preliminary numbers based on its weekly survey include between 8,200 and 20,000 flu deaths, between 140,000 and 250,000 hospitalizations, and between 15 and 21 million cases in the United States.

To be sure, that’s a lot more in terms of total numbers but a much lower mortality rate of about 0.008 percent, far below even the mildest pandemics. Between 3 and 4 percent of those infected with this coronavirus, unceremoniously dubbed 2019-nCoV, die from it, and about 25 percent get extremely ill. Those numbers likely will change as more data comes in. Estimates of mortality rates for past influenza pandemics have ranged from about 0.1 percent (1957 and 1968 pandemics) to 2.5 percent (1918 pandemic) to 10 percent (SARS) to 37 percent (!!!) for MERS.

This is a good illustration of the relationship between probability and impact. It is likely enough that this is a virulent enough strain that it could escalate even further, and fast. We don’t know enough yet about transmission or mortality rates of 2019-nCoV. But we do know enough to take it very seriously.

And we know the situation and what we know about it will continue to evolve quickly. Live updates are available at the Washington Post or The New York Times. Check out this excellent article from The Lancet for more on this virus. You can bet there will be lots of ongoing coverage on other media as well. Wherever you get your news, watch out for overly politicized or hysterical accounts as well as any that pooh-pooh the threat. And just toss out anything that claims nobody could have seen it coming.

This article is part of my new LinkedIn newsletter series, “Around My Mind” – a regular walk through the ideas, events, people, and places that kick my synapses into action, sparking sometimes surprising or counter-intuitive connections.

To subscribe to “Around My Mind” and get notifications of new posts, click the blue button on the top right hand on this page. Please don’t be shy about sharing, leaving comments or dropping me a private note with your own reactions.

- The Gray Rhino Wrangler on Substack - January 1, 2025

- Gray Rhino Risks and Responses to Watch in 2024 - January 10, 2024

- In the Media 2023 - December 31, 2023