A lot of people tell me that innovation goes nowhere at their organization because their management is too risk averse. That may feel true, but it’s imprecise. All managers should be risk averse. The most innovative companies are also risk averse. They don’t take risks they don’t have to, and they find ways to minimize or mitigate the risks, including those from innovation.

Managers who refuse to do any innovation are uncertainty averse, which is not the same thing as being risk averse. Innovation only happens in conditions of extreme uncertainty, because by definition you are creating and validating something that hasn’t existed before. That’s scary, because we’re human.

Our brains have, very literally, evolved to protect us from uncertainty. But because we’re human, we can train ourselves to differentiate between uncertainty and risk, and to reduce our aversion to uncertainty.

Being uncertainty averse is not a viable management stance. There is always uncertainty in any endeavor, even ones you’ve done a million times. Wall Street trading bots could go rogue and your company could lose millions of dollars. The same thing could happen, but only to your competition. Your CFO could be hit by a bus. Your COO could have a brilliant idea that saves the company millions. A flaming cow could fall from space and destroy your server farm.

Yet, corporate incentives often require that managers reduce uncertainty in both the execution of repeating mission and the development and adoption of new capabilities, i.e., innovation. That’s an incentive mismatch with reality, but in many organizations, one bad surprise can mean your career.

It’s no wonder people view uncertainty as risk and become uncertainty averse.

In my role as a futurist and in my role as an innovator, I must be absolutely clear about the difference between risk and uncertainty, how to determine the likelihood of each, how to forecast outcomes, and how to set up a situation with the least amount of damage and/or highest amount of return.

Surprisingly often, when we develop a clear definition of the business space, gray rhinos stand out…and when they do, we can define the risk they pose and get some idea of how certain we are about them.

Naming things accurately

Let me define my terms: Innovation is a new capability (thing, service, connection, approach) that gets used, and creates or captures value. (I’m paraphrasing the OECD’s definition, which condenses most of the the useful definitions. You can find an overview on Wikipedia, of course.) Because it’s new, there’s always uncertainty while making it; the degree of that uncertainty can be expressed in probabilities.

If the innovation fails, will there be a bad outcome? That’s the danger.

Can you mitigate the danger before it hits? Can you reduce the probability of the bad outcome?

Once you’ve figured out mitigation strategies and probabilities, you can look at the uncertainty again and determine risk. In traditional business management, the formula is likelihood (uncertainty) x impact (danger) = risk.

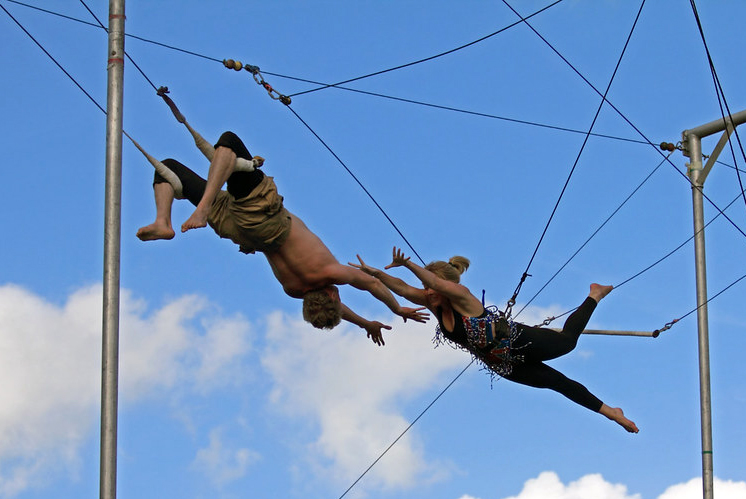

Here’s a metaphor for the difference between risk and uncertainty: Imagine two trapeze artists in mid-air. They are swinging toward each other, arms outstretched…but one of them is flying free and the other has his legs hooked over his trapeze.

They both are facing the same uncertainty: Will they make the catch? But obviously one is more at risk than the other. While the uncertainty of the catch is equal for both, the risk of falling has been mitigated for one. His biggest risk is that he will have to find another partner.

You can assume a net if you want; that would be another mitigation against ugly failure. It won’t mitigate audience disappointment in the failed catch, though…so let’s add a mitigation for that uncertainty, and say that these two athletes practice a lot.

To be even more risk-averse, let’s make sure they practice with safety cables, and they work with each other for level of trust necessary to pull off this move close to 100% of the time. They can now do the audience-wowing stunt with a minimal amount of risk.

If you’re in management, or if you can talk to your management, try using this metaphor for how to do innovation. If you’ve hit a fatal risk (missing the catch and falling), it means you didn’t do enough, or the right, preparation earlier in the process. For the acrobats, that means practicing and maybe installing a net.

Doing the Right Work Early On

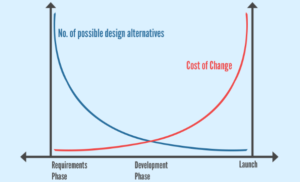

For the innovator, inside an organization or not, that means doing the work early on to ensure that you are solving the right problem, that you are designing something that is usable, feasible, and desirable, and that you have the right team. The more development you do, the higher the cost of change, and the greater the risk; addressing as many uncertainties as possible as early as possible is a cheap and fast way to power through those uncertainties before they become costly or dangerous risks.

Unfortunately, this approach is the exact opposite of the approach needed to deal with repeating mission execution.

There should be very little uncertainty about your organization’s current main business – yes, a flaming cow might fall from space, but barring that, you fill out your timesheet the same way you did last week.

You send documents to the printer the same way you did yesterday. Your factory produces rolls of 200, 400, and 800 speed film the same way it has for years. You shouldn’t need to practice for months each time you do one of these.

Running a Parallel Process

When you see an incoming gray rhino, though, you are going to need a parallel process that runs alongside your main mission, one that front-loads all your assumptions and beliefs about how to deal with the gray rhino, tests them as rigorously and as fast as possible, validates which approach has the highest probability of success, and works out the risk ahead of impact. (The Impact, Likelihood, and Velocity Model from Georgetown University is one of my preferred methods.)

I’m a big fan of starting with Human Centered Design and problem deconstruction, then moving to Lean Startup, but many approaches can work.

Agile development, done right, can help you develop new software with little risk. It can tell you how to build it, but not what to build, so you’ll still have to test your assumptions. It may seem like a lot of work up front, but this approach reduces uncertainty and saves time, money, and pain later. Don’t put unpracticed people on trapezes in front of a live audience.

And remember: the biggest risk of all is not innovating.

This article has been adapted from a post at InBLOGnito and is used with permission of the author.

Latest posts by Raq Winchester (see all)

- GUEST POST: Is It Risk or Uncertainty? The Answer Matters - April 9, 2019