The Business Roundtable got a lot of attention from its recent statement that the purpose of a corporation was not just to protect shareholders’ interests but also those of a much wider set of stakeholders.

Nearly 200 CEOs committed to a new set of principles that include delivering value to customers, investing in employees, dealing fairly and ethically with suppliers, supporting the communities in which they work –and last, generating long-term value for shareholders.

Reactions included both praise and criticism.

Some naysayers claimed that the statement didn’t go far enough, citing its omission of any comment on the need to curb executive compensation.

Others suggested that it was mere window-dressing –like Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who issued a statement that the new wording was welcome but meaningless without action. The New York Times reported. “These big corporations can start following through on their words by paying workers more instead of spending billions on buybacks,” she said.

Others still, like the Council of Institutional Investors, denounced it, saying it undercut managerial responsibility to shareholders and that “accountability to everyone means accountability to no one.”

I am among those who applaud the new principle, and could not disagree more with the notion that being accountable to both shareholders and stakeholders is mutually exclusive.

In New York City last week, I was delighted to learn from two former Nike executives about an approach that makes this case far better than I can.

Lisa MacCallum and Emily Brew, co authors of the recent book, Inspired INC: Become a Company the World Will Get Behind and co-founders of the consultancy Inspired Companies, gathered together a group of investors and other key stakeholders for an important conversation about the role of companies.

Their first question was a challenge to think about a company we love and would evangelize for, and another one that we cannot stand.

(Mine? On the first count, my favorite Moroccan restaurant, Tagine, where I go nearly every time I visit NYC, where they know me and I know I can eat safely. And on the second, Bob’s Red Mill, the purveyor of supposedly gluten free baking goods that for years used wheat to make a key gluten substitute, didn’t have the courtesy to disclose it on the label, and pooh-poohed complaints of customers with celiac disease -including me- who had gotten sick from their xanthan gum.)

These two categories of company illustrate exactly why it’s important for companies to take into account key stakeholders -and why shareholders benefit when they do and suffer when they don’t. The first kind can accidentally stumble but its customers will help pick it back up again; for the second, a crisis can turn into catastrophe.

MacCallum and Brew talk about the “New CEOs”: instead of Chief Executive officers, these are Consumers, Employees, and traditional Outsiders –all of whom need much more attention than traditional business models afforded them.

Failing to take these new CEOs into account is simply poor reputational risk management that ultimately destroys value. Social media means that reputations can rise or fall on the whims of a viral tweet –and failing to take into account stakeholders can make the difference between strangers piling on in the attack or rising together in a company’s defense.

MacCallum and Brew cite studies showing that out that only one in 10 people has a lot of trust in major corporations. Further, 21 percent of US employees say they don’t trust their employers. This rises to 40 percent in France and 43 percent in Japan.

Those are the people whose livelihood is tied to the well-being of their companies. Just think of the customers and outsiders whose loyalty does not lie in a paycheck. But too many companies don’t think of any of these three groups.

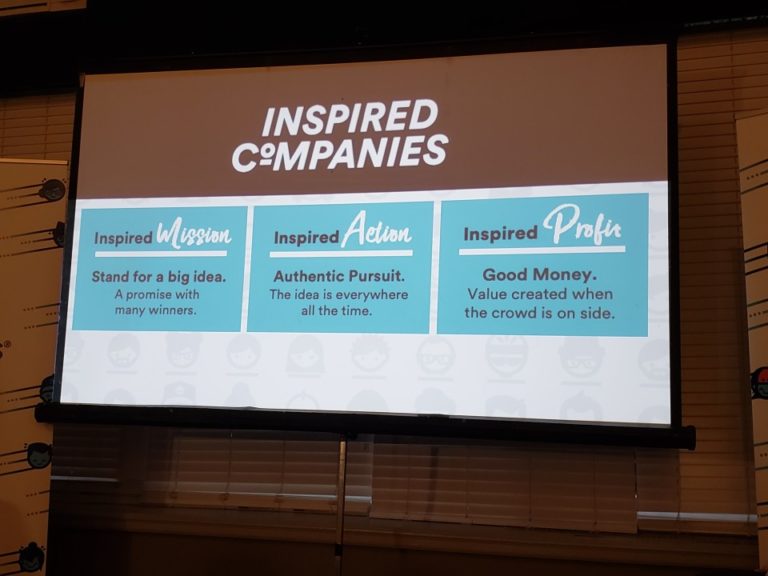

MacCallum and Brew’s solution is for companies to focus laser like on having an inspired mission that they turn into action -and which ultimately leads to profit. They provide a framework for how to do this but also warn how not to.

Uninspired companies “spend a disproportionate amount of time looking for new ways to extract profit from customers, the environment, business partners, and workers instead of creating additional value,” MacCallum and Brew write. “They will increasingly encounter external stakeholders who are difficult to work with, and have declining customer bases and uncommitted employees.”

Companies thus waste resources on “reactive crisis management, constant onboarding to manage turnover, scrutinizing and monitoring business partners, and scrambling to eliminate the hurdles government and society put in the way.” The result? Falling returns and, ultimately, failure.

“Everything an Inspired Company does comes back to the relentless pursuit of an inspired mission. It is wired to disproportionately prioritize day-to-day decisions through the lens of the big idea it holds. Investments and divestments, hires and fires, innovation and transformation are all geared toward delivering the mission,” they write.

The free-market economist Milton Friedman has been quoted widely on his argument that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.”

But increasing profits without a mind to mission and stakeholders is a fool’s game. Ultimately, it will be self defeating -and a risk not worth taking.

This article is part of my new LinkedIn series, “Around My Mind” – a regular walk through the ideas, events, people, and places that kick my synapses into action, sparking sometimes surprising or counter-intuitive connections.

To subscribe to “Around My Mind” and get notifications of new posts, click the blue button on the top right hand on this page. Please don’t be shy about sharing, leaving comments or dropping me a private note with your own reactions.

- The Gray Rhino Wrangler on Substack - January 1, 2025

- Gray Rhino Risks and Responses to Watch in 2024 - January 10, 2024

- In the Media 2023 - December 31, 2023