Why are people so prone to denying instead of dealing with the obvious problems in front of us, whether coronavirus or climate change or financial fragilities?

Last week I wrote about the five stages of a gray rhino crisis, the first one being denial. This week I want to dive a lot deeper into denial: Why do we do it? Why are some people more prone to it than others? And most important, how do we snap ourselves and others out of denial as soon as possible?

Denial is a powerful force, often rooted in primal emotions. It’s a protective quirk of human nature: often if we fully accepted the extent of some shocks all at once, it would be too much. Denial allows us to function so that we can gradually move toward acceptance. If it works as nature intended and only sticks around temporarily, denial can be helpful. But if it does not dissipate, denial can be catastrophic.

All of us deny to different degrees and deal with shocks in our own ways, but none of us is immune. To be honest, though I spend my days thinking about the crisis we are in and sharing my insights with others, I am in a semi-numb state in which the reality hasn’t completely hit emotionally –though the tension in my neck and shoulders suggests that it’s registered physically.

My way of dealing with difficult situations is to think them through, and I could reasonably be accused of over intellectualizing at times: that’s my coping strategy. It takes effort for me to embrace the emotional side. I remember not crying until weeks after a close friend’s funeral. It took that long after losing her to get past my defenses.

Part of understanding why you and those around you deny a problem is to recognize that there are both emotional and logical components. It’s also true that sometimes “logic” doesn’t work the way we think it should; we might think we’re reasoning through when we’re being irrational, responding to deep-seated biases and defense mechanisms.

But there are things that can break through the shield of denial. Emotion and human connections are the most powerful, especially combined with some of the other strategies below.

Emotional connections. The more people start seeing those they know and the closer those relationships are, the more likely they are to take the virus seriously.

Over the past few days, I’ve seen a steady increase in mentions of friends and relatives of people I know who are dying from the virus. At least three friends have contracted it and, luckily, are in late stages of recovery.

Manu Dibango, a global treasure, just died from COVID-19 related complications.

The number of global and local public figures being diagnosed is rising: Prince Charles, the husband of Sen. Amy Klobuchar, the wife of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the physician of German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and many more. Though the vast majority of people are not close to them, the more recognizable figures are affected, the harder it becomes to ignore the reach of the virus.

Thinking of others. When I used to run a not-for-profit organization and was getting a crash course in fundraising, one of the important lessons I learned about asking for money was that it was much more comfortable remembering that I was not asking for myself, but for a bigger cause to support others.

In fact, research suggests that urge people to stay home because of others’ safety is more effective than warning them about the danger to themselves. Part of that is because humans are biased to be overconfident of our own ability to manage a situation.

So we can see dangers better when we imagine how they will affect other people, especially those close to us. Take a look and listen to this powerful 18 second message and just try to tell me it doesn’t move you:

I’ve spoken with friends with chronic medical conditions and ongoing needs who are worried that they will not be able to get regular care like plasma infusions or cancer monitoring, because their doctors have closed their offices, or because they are afraid of exposing themselves by going in to a medical facility. Since I suffer from celiac disease, intermittent asthma, and other autoimmune challenges, I can relate all too well.

Staying home, urging others to do so too, countering misinformation and spreading the best information I can find all help the many vulnerable people about whom I care even a little bit –and everyone like them.

Recognizing manufactured denial. Sometimes the wrong people understand all too well the depths of our human biases and how susceptible we are to information we want to hear –and they use their knowledge to manipulate us.

The late German sociologist Ulrich Beck wrote about the way governments and media “stage” risks: they portray risks the way they want us to see them, which generally is the way that is to their advantage, rather than as these risks are in reality.

The historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway have shown eloquently how this works in their book Merchants of Doubt about how corporations have sown disinformation about climate change, tobacco and more.

It’s clear that there are partisan differences in perceptions of the coronavirus, in part because people of different political persuasions tend to go to different news sources. Perceptions within each party vary as well depending on which media they relied on to get information.

How do you combat manufactured denial? Be aware of it. Watch media from different perspectives, including those you may not agree with. Ask yourself who benefits from a particular narrative and how self interest shapes the story you are hearing.

Peer pressure. Behavioral economists talk about groupthink, the phenomenon whereby groups are likely to suppress dissenting opinions –particularly in groups that do not include diverse backgrounds and perspectives. Groupthink can reinforce denial –or it can encourage buy-in.

While groupthink often involves bias of which group members are not aware, peer pressure is an active process of getting group members to conform. It can either counter our natural tendency toward denial or reinforce it.

All those pictures of college kids on spring break on the beach and on boats, most definitely not practicing social distancing, is an example of how peer pressure can have a negative effect. But the more people come out and say that they are staying at home, washing hands regularly, avoiding unnecessary social contact, the more others are likely to do so too.

Fans of The Bachelor franchise may have noticed a tension in this dynamic between stars of recent seasons who are partying hard in Florida as part of a group that calls itself “the quarantine crew” and scolding by former Bachelor Nick Viall, who suggested that they were not being good role models by their blatant disregard of social distancing recommendations.

On Facebook, I recently followed the lead of a friend who added a “Stay Home. Save Lives. #quaranteam” frame to their profile picture. While during past crises many people have derided Facebook “slacktivism,” right now the platform has potential to reinforce the message that many people do take the crisis seriously. But users also need to be vigilant about combating a flood of misinformation.

Visual imagery. Research shows that social media posts with images are more likely to be shared than text-only posts. Other research shows that people retain significantly more information from visuals than from words alone. The power of visual imagery can be helpful for combating denial.

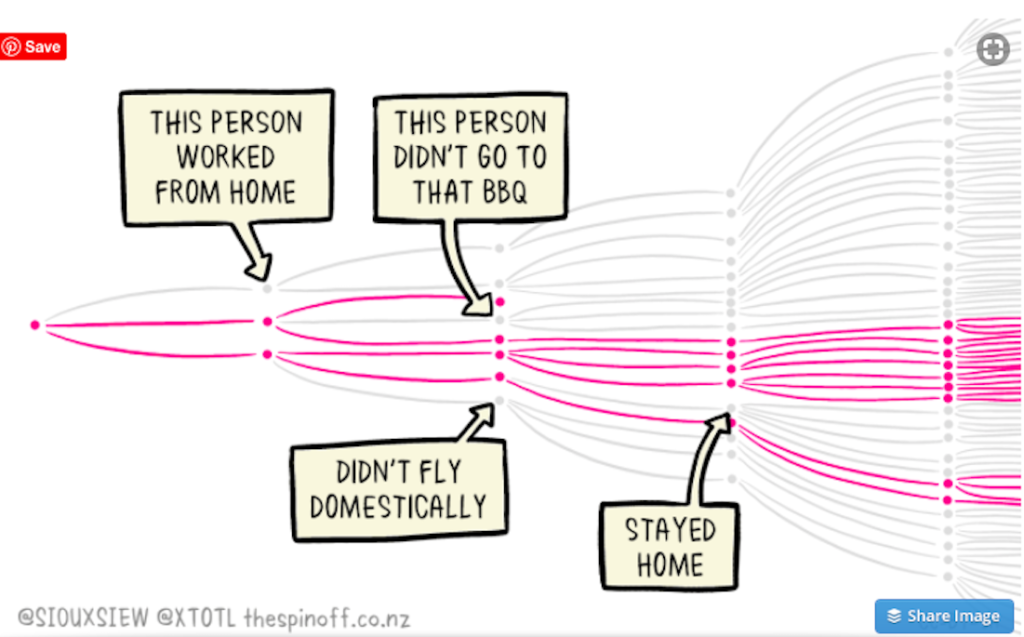

This is one of the best graphics I’ve seen to illustrate how social distancing and shelter at home can combat the virus:

Similarly, Tomas Pueyo’s viral essay, The Hammer and the Dance, is chock full of powerful charts and graphs.

And my personal favorite is the Sesame Street character, Grover, giving a great demonstration of how to do social distancing:

I hope that some or all of these insights are useful, either in fighting off your own denial or in convincing the naysayers around you to join in an effort that depends on everyone doing their share.

For more about denial, see Chapter Three of THE GRAY RHINO: How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore.

This article is part of my new LinkedIn newsletter series, “Around My Mind” – a regular walk through the ideas, events, people, and places that kick my synapses into action, sparking sometimes surprising or counter-intuitive connections.

To subscribe to “Around My Mind” and get notifications of new posts, click the blue button on the top right hand on this page. Please don’t be shy about sharing, leaving comments or dropping me a private note with your own reactions.

- The Gray Rhino Wrangler on Substack - January 1, 2025

- Gray Rhino Risks and Responses to Watch in 2024 - January 10, 2024

- In the Media 2023 - December 31, 2023