My Facebook and Twitter feeds were chock full of “Vive la France!” posts Sunday as the word circulated of centrist Emmanuel Macron’s election as the next president of France. Macron roundly defeated Marine Le Pen.

Fractures within the European Union ranked as the third most important obvious but unresolved “gray rhino” threat of 2017, in my annual review of major top risks lists compiled by risk and investment experts at the beginning of the year.

France’s election marks a major inflection point in the unfolding of European political -and thus economic- risk. While polls had showed Macron with a wide lead, after the Brexit and US presidential votes, many analysts were reluctant to rule it out completely.

Breathing a collective sigh of relief along with others who fear the socio-economic consequences of a fracturing European Union, I can say with confidence that this was:

A win for rational thought over hateful rhetoric.

A win against Russian hackers.

A win for the European and global economies (at least for now…)

A win for the winds of change when it comes to sclerotic existing party systems and the status quo.

This week is indeed one to celebrate. But then it’s time to put the champagne away and focus on the tough work and many remaining uncertainties ahead. Despite his solid victory, Macron faces headwinds, as he has neither an established party nor experience in elected office. French parliamentary elections in June will determine how much leverage he will have to deliver needed economic growth.

To be sure, Macron’s win is the third victory in a row for moderate, pro-European forces over resurgent right-wing nativists. In Austria, Norbert Hofer, the candidate of the anti-immigrant Freedom Party lost December’s presidential election. The Netherlands in March rejected right wing Geert Wilders in favor of sitting Prime Minister Mark Rutte.

But the far right is far from defeated. And it’s important not to overlook obvious signs of troubles to come.

Marking a historic high for her party, Le Pen doubled the percentage of votes her father got in his 2002 loss to Jacques Chirac. Turnout was low, reflecting many voters’ frustration with the choices available. That could make for a fractious parliament once elected.

In the Netherlands in March, lost in the headlines over Wilders’ defeat was the detail that his Party for Freedom (PVV) gained five seats and Rutte’s Liberal Party lost eight. Several local parties are considering affiliating with the PVV. And a new party, Forum for Democracy, founded by public intellectual Thierry Baudet, is also anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant, and anti-EU. Dutch voters describe him as “the intelligent people’s alternative to Geert Wilders.”

And in Austria, the Freedom Party (FPÖ) has been gaining support. Unlike Le Pen’s decisive defeat, the fact that Hofer came so close to winning –with 46.2% of the vote- means his supporters and party will are far from likely to go away. Remember as well the November polls that showed 44% of Austrians thought their country needed a Trump of its own.

These are the things that worry not only investors and travelers who like the ease of crossing borders within Europe, but also observers of history who understand how important the European Union is to preventing cataclysmic conflict like the second World War.

And then there’s the question of Germany, which as the EU’s largest economy has been the anchor –in both good and bad senses- of the euro.

What do the recent elections mean for Germany? It’s no accident that Chancellor Angela Merkel, the embodiment of a steady hand and the status quo, was the first leader of another country to congratulate Macron and proclaim a victory for “a strong and united Europe.”

She faces re-election in September, and some polls earlier this year have even suggested that she will lose the September 24th vote.

But Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union is doing well, with a strong victory in a regional vote in late April. The far-right Alternative for Germany party has plummeted in the polls in recent months.

And her strongest challenger, Martin Schulz, of the Social Democrats (SPD) has given back some of an earlier lead in the polls. But even if Schultz and the SPD were to regain momentum and win, the choices are nowhere near as stark as what France, Austria, or the United States faced. Schulz, far more skilled at appealing to voters’ emotions than the steely Merkel, has cultivated a “man of the people” image. But as a former president of the European Parliament, he is no Euro-skeptic.

France voted for change but not massive disruption. A lot can happen between not and September, but it is far from impossible that Germany will do the same.

Can Europe move to strengthen regional ties while creating enough jobs to beat back nationalism and xenophobia?

The recent elections have given the EU some badly needed breathing room and momentum. But this is no time to become complacent about the remaining tensions within the European Union, which remain one of the biggest risks facing the global economy and security.

And then there is Italy, whose elections are still a year off, but could well bring a far-right, anti-EU party into power in the next major battle for Europe’s future. Amid a banking crisis, political crisis and weak economy, the “sovereigntist” opposition Five Star movement which is anti-euro, anti-vaccine, anti-immigration,, anti-NATO, and generally anti-establishment, has enjoyed a surge in power.

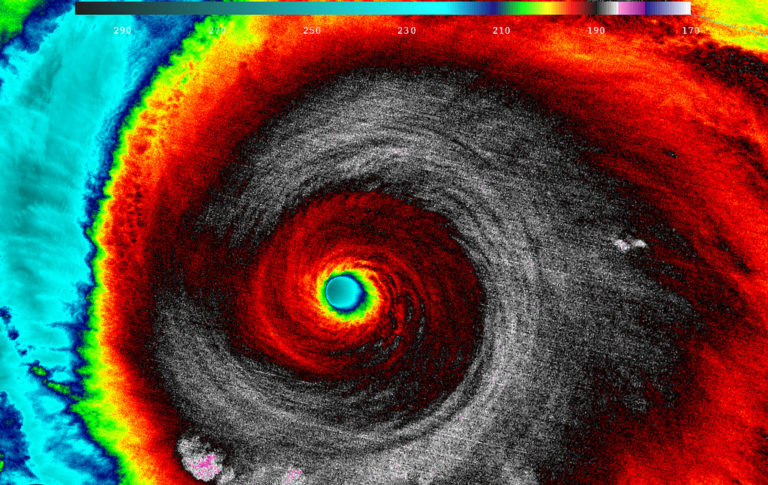

The moderates elected this year will have to deliver results quickly, or we could just be experiencing the eye of the storm.

- The Gray Rhino Wrangler on Substack - January 1, 2025

- Gray Rhino Risks and Responses to Watch in 2024 - January 10, 2024

- In the Media 2023 - December 31, 2023