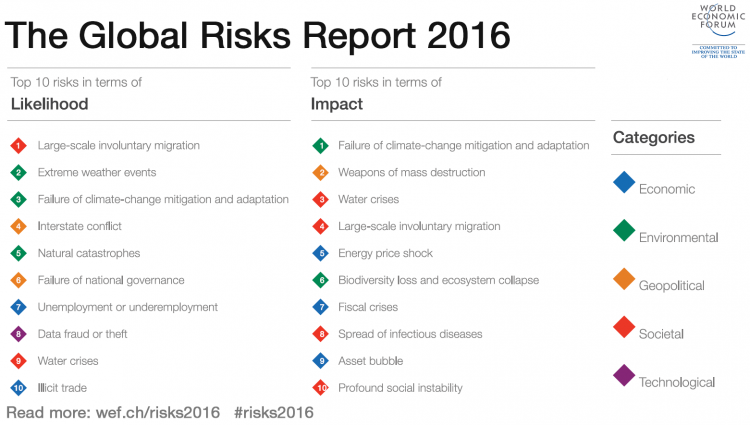

The top right hand quadrant of the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Risks Report is home to highly likely, high impact dangers that have not been resolved: climate change, weapons of mass destruction, water scarcity, mass forced migration, and energy price shocks. All too often, policy and business leaders neglect risks like these even after recognizing them.

I call these risks “Gray Rhinos”: large, dangerous and heading straight for us. Unlike a certain large fowl that people can only envision if it’s the right colour, black rhinos are no more black in colour than white rhinos are white. They are all grey: something that is so obvious, yet too often missed.

Since I introduced the concept of the Gray Rhino at a Thinking Ahead talk at Davos in 2013, conversations with leaders around the world have helped me develop a framework to understand the progression of Gray Rhinos and strategies for overcoming them. This framework can improve our ability to confront large-scale risks in business, organizations and policy-making.

Five stages

Gray Rhinos fall into categories that differ by degree of complexity and consensus (or lack thereof) on how to solve them. Responses to Gray Rhinos lie along a five-stage continuum that begins with denial and, if we are lucky, progresses to action. Each stage has its own obstacles and opportunities, which in turn shape strategies for avoiding a trampling or, even better, finding a new and profitable path.

Like the five stages of grief outlined by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a Gray Rhino begins with denial, which both enables us to deal with shocks by absorbing them gradually but also delays our responses. By the time a risk has made it to the top right hand quadrant of the Global Risks Report, it is safe to say that a critical mass of leaders have transcended denial. Yet it is far from a given that all stakeholders or citizens have moved past this crucial first hurdle.

The second stage – in which we recognize a problem but find reasons not to deal with it promptly – is muddling. The tricky third stage, which happens once we’ve recognized the need to act, involves diagnosing: understanding the causes and finding the right solutions. The fourth stage, panic, is when the crisis is at hand; it is a double-edged sword that creates the urgency that can lead to action yet warps our decisions so that we are less likely to make the right choices. The final stage, action, sometimes doesn’t happen until after a trampling. Often by the time we spring into action it is too late; yet it is not impossible to act in time to avert a catastrophe.

The failure of climate change adaptation and mitigation – cited as the most impactful and the second most likely risk for 2016 – is an example of a Gray Rhino spanning the five stages. It is an inconvenient truth: one where the solutions are clear, the costs of solving the problem are high, and the costs of ignoring it are higher.

After decades of denial, global leaders seem to have reached a critical mass in their resolve to shift from complacency into action. Record world temperatures, “weather weirding”, and the persistent efforts over years by key influencers finally achieved a global agreement in December to engage business, investors and all levels of government in reducing carbon emissions. The accord doesn’t go as far as is needed, and compliance will take major efforts. Nevertheless, it is a milestone in efforts to confront a Gray Rhino.

The second biggest risk in terms of potential impact – though seen to be the second least likely to occur – is the spread of weapons of mass destruction. North Korea and the possibility of these weapons falling into the hands of non-state actors remain serious issues. Yet the recent Iran nuclear accord is an example of an action in response to a highly obvious challenge; it is not perfect, but in the eyes of many decision-makers, it’s the least-worst scenario.

Deemed to be most likely – since it is a reality – and the fourth most impactful of the risks in the report, the forced migration crisis straddles the Gray Rhino stages of muddling, diagnosing and panic. Solving the migration crisis, of course, means stemming the wanton violence and human rights violations in the countries migrants are fleeing.

Policy-makers’ seeming inability to come up with a way forward, much of it rooted in disagreement over the fate of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, has dangerously prolonged the muddling phase of the crisis. Lacking a clear shared diagnosis and feasible solution, the Syrian crisis has devolved into panic as millions of refugees have sought safe haven in Europe and elsewhere.

Diagnosing the causes of the unrest in the Middle East also leads to a set of problems that join together into a Gray Rhino of many parts, a Chimera-Rhino, if you will: inequality, water and food shortages, youth unemployment, governance and political instability. When risks are interconnected, they magnify each other. They also increase the likelihood that leaders will try to kick the can so far down the road that we end up facing bigger catastrophes.

The panic stage of a Gray Rhino often combines a sense of urgency to act with impeded judgment, and thus often worsens the situation. In this case, Islamist militants, who see refugees as traitors, are capitalizing on the pull-up-the-drawbridge responses by populist politicians. It’s an oversimplified non-solution to a complex, inter-connected problem.

Interconnected risks

The section of the Global Risks Report that identifies interconnections among risks is valuable for prioritizing and strategizing. The more closely tied a risk is to others, the harder it is to prioritize among problems that need to be addressed together. When a risk is at the beginning of a chain that creates domino problems down the line, it should be high on leaders’ list of priorities.

Water scarcity, for example, can lead to social unrest, spread of infectious diseases, food crises and forced migration, and has roots in poor urban planning and failure of climate change adaptation. Water crisis is the third most impactful risk in the report, and the ninth most likely – though in places like Brazil, California, and Flint, Michigan, it already is a reality.

Similarly, energy price shocks are complex in their causes and effects, tied to deflation or inflation, asset bubbles, fiscal crises, and food and water scarcity. Falling oil prices have already hit hard the budgets of oil producing states and could lead to increased social instability. They have hit shale producers, cutting production and jobs, and contributed to warnings of pending defaults by energy-sector borrowers.

But are the rapid swings of energy prices a risk in and of themselves? For my money, they are merely a symptom of a power struggle related to the decline of fossil fuels. A mix of slower economic growth in China, greater efficiency in energy use, and new energy sources sparked the drop in energy prices. Oil producers then accelerated by adding to a global gut intended to slow the entry of new energy producers. Yet they are only postponing the inevitable as old technologies and trends give way to new ones. The real Gray Rhino here is dealing with the growing pains of creative destruction. Our focus, then, must be on easing the transition and finding other ways to mitigate the knock-on effects of energy price swings.

Changing energy trends, like so many Gray Rhinos, are an opportunity for some and a threat for others. The most successful leaders are the ones who can find the opportunity to solve a problem and run with it, for problems and solutions are intertwined.

The Global Risks Report is an important tool that helps business, civil society and government leaders take stock each year of the biggest Gray Rhinos facing the world. It’s a road map for issues on which leaders can seize momentum towards change, and where they need to focus more on changing perceptions so that we can better act on obvious, unresolved risks.

Originally published on World Economic Forum Agenda, February 2, 2016

- The Gray Rhino Wrangler on Substack - January 1, 2025

- Gray Rhino Risks and Responses to Watch in 2024 - January 10, 2024

- In the Media 2023 - December 31, 2023