I was on a Zoom call about Chicago’s economic recovery at 3:43 pm yesterday afternoon when my cell phone buzzed with an emergency alert from the city: Tornado warning til 4:30 pm Central Time.

Having grown up in Missouri, Wisconsin, and Texas, I remember having spent many hours in the basement (or in the middle hallway in Texas, where few homes had basements because the limestone underground made digging too expensive) when I was young sitting out tornado watches and warnings with a flashlight and radio waiting for the all-clear.

Earlier I had moved the plants on my deck to a safer place because I knew a storm was coming after a few days of 90-degree weather and a forecast of a front coming through with high winds.

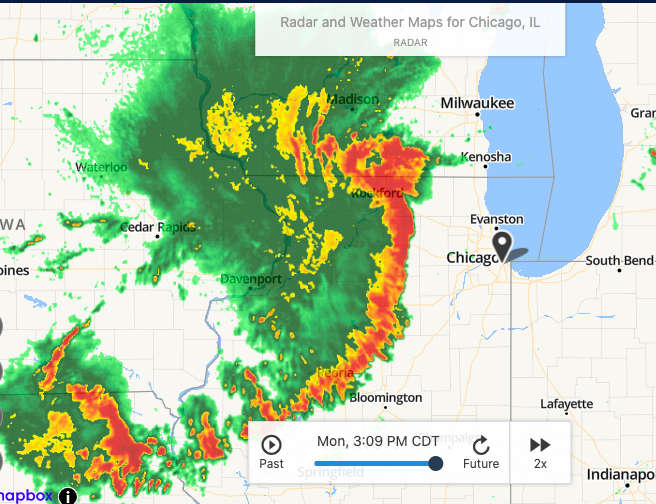

A fresh look at the weather radar showed a daunting storm system headed my way.

A few minutes after the city emergency text alert, I heard the tornado sirens power up and start wailing. I’d never heard them outside of the monthly Tuesday morning tests. Nor had my neighbor, who has lived in this neighborhood for more than 30 years.

Nevertheless, I had a hard time processing the information about this imminent threat. Sure, there were several tornado watches along with severe storms every summer. But conventional wisdom was that right by Lake Michigan, where I live, tornadoes simply didn’t hit.

I could feel the battle inside my head around the cognitive dissonance between what I thought I “knew” and this very real, imminent threat. It was ironic because of the question that has consumed my professional life for the last several years: why people fail to act on the obvious dangers coming at us -whether a giant gray rhino or, in this case, a massive summer derecho storm system stretching for hundreds of miles and spawning funnel clouds every which way.

It was exactly the kind of cognitive tug-of-war that all of us face when confronted with inconvenient risk information that we would rather not have to confront. Emotion versus reason. Cognitive biases versus self control and willpower. The process was not so different from the pandemic-related mental clashes we’ve all been managing over the past several months.

Thankfully, reason took over. I live on the top floor of a classic Chicago-style three-story building, surrounded by windows. If a tornado were to hit, my apartment was not a safe place to be. So, reluctantly, I threw my laptop and wallet into a backpack and headed down to the basement with my dog who seemed at least as confused as I was.

My neighbors were out watching the storm roll in until taking cover at the last possible minute. I’d checked and saw the storm was supposed to hit at 4:05 pm, which it did pretty much on the dot. The sirens stopped wailing just as the rain started and I ducked into the basement.

After a torrential downpour, the rain slowed a bit and then came the thunder and lightning with sirens wailing again.

I tried calling my sister, who lives in a suburb just south of Chicago, but her phone was down. Checking social media, I panicked at a friend’s post that you should crack your windows during tornado warnings in case of pressure changes that can explode the windows. I berated myself for not having remembered that tip from all of my childhood Midwest storm skills, and then for being silly for berating myself for not remembering something from so long ago. At any rate, it was too late to go back upstairs safely, so I crossed my fingers.

The worst of it was over in half an hour or so. I texted with a friend who was stuck out driving in the storm and had gotten word of a funnel cloud touchdown a couple of miles from me, with another who lives in a high rise next to the lake, and another whose power had just gone out.

After the warning expired, I came back upstairs and watched the wind whip around the branches and leaves outside of my windows.

When the sun re-emerged an hour or so later, I took my dog out for a walk and a look at the damage in the park nearby. A tree and several big branches had come down, but compared to the Rogers Park and Logan Square neighborhoods, it was nothing. News reports confirmed that there had been an actual tornado in Rogers Park, which then moved out over the lake and became a waterspout. More of my friends lost their power, and some don’t expect it back until the weekend.

I was glad that reason had taken over and made me go down to the basement, conquering my stubborn emotions that wanted to ignore the warning. In fact, the emotions that make us ignore warnings are closely tied to the emotions that make us fear the reasons the alarm is sounding. So it had not been just reason versus emotion, but emotion versus emotion: fear versus denial. To make good risk decisions we need to pay attention to all three components.

After the storm the emotion was a good one: a sense of relief.

This morning, the sun was spectacular. Closer to the lake, there were more downed trees. Most of the trash bins had been blown over, and a flock of seagulls was feasting on the mess.

This article is part of my LinkedIn newsletter series, “Around My Mind” – a regular walk through the ideas, events, people, and places that kick my synapses into action, sparking sometimes surprising or counter-intuitive connections.

To subscribe to “Around My Mind” and get notifications of new posts, click the blue button on the top right hand on this page. Please don’t be shy about sharing, leaving comments or dropping me a private note with your own reactions.

- The Gray Rhino Wrangler on Substack - January 1, 2025

- Gray Rhino Risks and Responses to Watch in 2024 - January 10, 2024

- In the Media 2023 - December 31, 2023